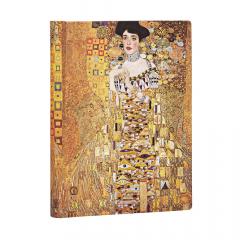

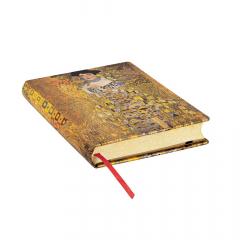

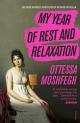

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), reproduced here, is an example of the Viennese “Jugendstil” style. With the subject’s face emerging from the background like a dream, the portrait is hauntingly beautiful. Seized by the Nazis in the 1940s, the painting was recovered and is now on display in New York.

2018 marked one hundred years since the death of one of the most significant artists of modern times, Gustav Klimt (1862–1918). To pay tribute to his daring artistic vision, we’ve created two Special Edition covers that spotlight his “golden phase.” During that period he painted these iconic pieces, destined to rouse instant recognition in both serious art lovers and those who simply have an appreciation for beautiful artifacts.

Klimt attended the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts where he trained as an architectural painter. As he painted interior murals and ceilings in public buildings, his technical ability endeared him to Vienna’s conservative haute society. But soon, his inner boundary-pushing style came through, causing too much of a stir for the culturally reactionary class who had initially welcomed him so openly. Three paintings he created for the University of Vienna were rejected – deemed “pornographic” – and so he took his talents elsewhere.

Klimt’s response to the scorn was to found the Vienna Secession, an avant-garde movement that treated art as a space for exploring possibilities rather than following the academic tradition. From then on, he was an artistic renegade contributing to the cultural fermentation of turn-of-the-century Vienna. He painted mostly portraits of the progressive society ladies who were his patrons. His works were often erotically charged, exotic, mystical representations, marking him as a Symbolist painter.

Klimt was firmly convinced that there should be no separation between so-called “low” and “high” forms of art. His canvasses were filled with organic forms reminiscent of the earlier Arts and Crafts movement as well as decorative patterns suggestive of Art Nouveau, both styles that were oriented towards this principle of universal art.

Although clearly unique to Klimt’s original style, his Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, reproduced here, still fits within the currents of Art Nouveau and Symbolism. The rich patterns are an example of the former style, while the suggestive symbols, such as triangles, eggs and eyes, remind us that Klimt was receptive to the newest ideas circulating in Vienna’s salons – the “Meetups” and “TED Talks” of the early 20th century. The liberal amounts of gold leaf that he used to fill the background and depict the armchair and woman’s gown were inspired by Klimt’s fascination with traditional Japanese art and the look of Byzantine religious mosaics that he saw during his travels to Venice and Ravenna.

For all the ostentatious quality of the painting, this portrait of one of Klimt’s patrons is a beguiling image projecting the strength and sovereignty of Vienna’s society women. As a symbol of its vibrant time, it is an essential addition to the Paperblanks archive of artistic and cultural heritage.